Why do our noses run when it's cold?

The secrete life of mucous. Bonus free idea: a Meat Loaf/Wheatus tribute band called Meatus.

I went for my walk on Tuesday slightly underdressed, as I am often wont to do thanks to a case of what I call “eternal weather optimism”. What can I say? When the sun’s out, it’s automatically 14 degrees and a light sweatshirt is more than enough. Until I get out there and it’s 6 degrees and breezy. (Since it’s time to reacclimatize my body to exercise after many months of…not, I more than made up for the discrepancy in temperature with a surplus of lactic acid and heavy breathing.)

This sums it up pretty well:

So there I was, wheezing along with my walk-run-walk pattern, overtaking then getting passed by the same group of youths for much of the sea wall stretch of my route, then getting the eyebrow from passersby and their dogs, both wearing winter coats. My ears were doing much of the heavy lifting with a mask, headphones, half-fogged sunglasses, and a hat all piled on top of each other. My last shred of dignity quickly evaporated when it became clear that my nose knew it was only 6 degrees, not 14, and decided to run under my mask.

Why is this a thing, I thought as I dismantled the entire head-related operation to get it under control. Spring blooms might be out in Vancouver but my allergies sure aren’t. I’m (thankfully) not sick with anything. Nope, it was the type of nose running that happens during a school ski trip or in the walk from the car to the hardware store in the dead of winter. The cold-induced inconvenience surprised me since the day didn’t strike me as that kind of cold.

I looked into it and, surprise, there are good reasons for why the body does this to us, including but not limited to condensation and temperature differential. Get ready for lots of references to the word mucous!

The nose is a complex system. So complex, in fact, that at least one of the anatomical names for its many structures includes the word labyrinth. There are some real alien-looking forms in there secreting all kinds of fluids and making it possible for us to do basic human things. Basic life form things, actually. Noses and nasal cavities play seriously important roles that go beyond just breathing and smelling. I’ll run down the major segments and what they do so that later we can talk about what’s going on when the nose decides to run.

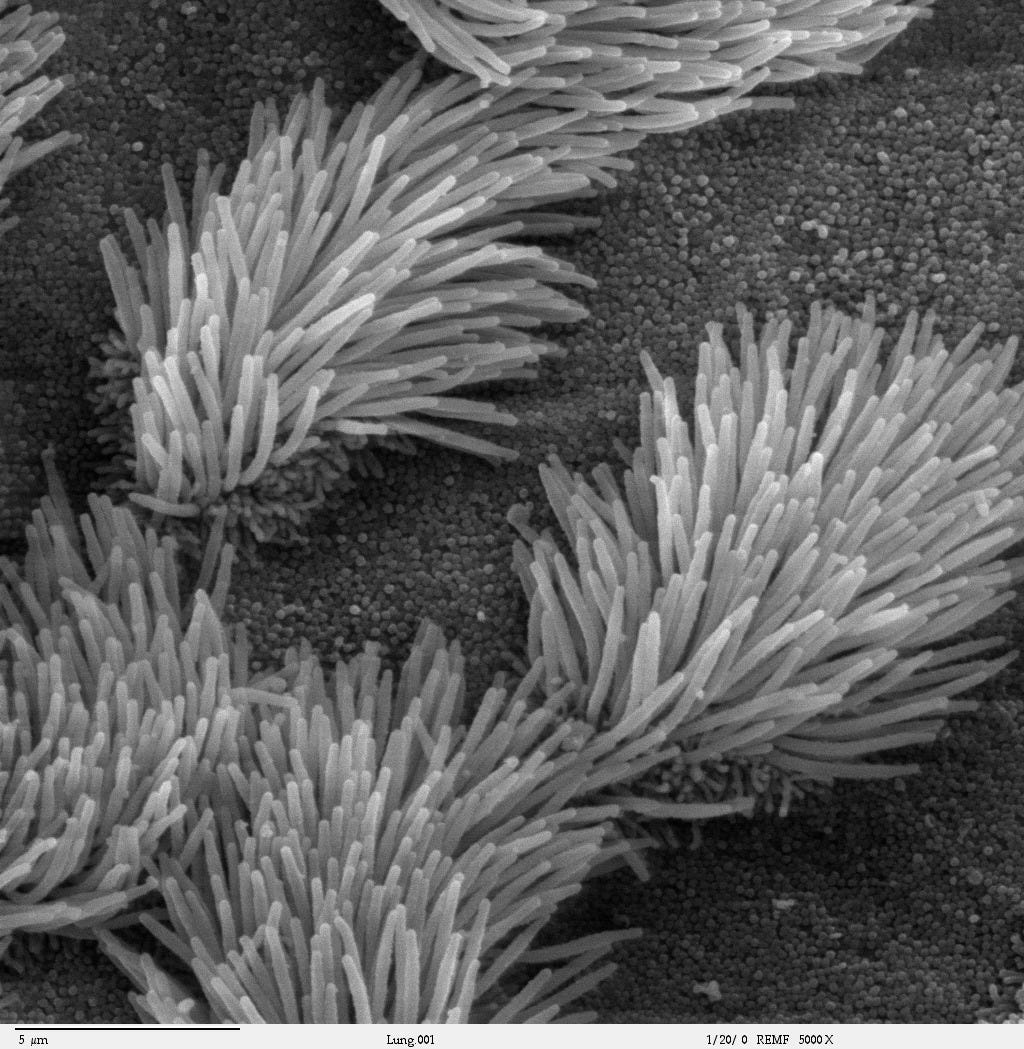

Smell, or, the olfactory segment. A patch of specialized cells about 3x3 cm in size lives at the top of the nasal cavity in the area closest to the brain, behind and above the nostrils. This area is called the olfactory epithelium. Microscopic cilia extend out from the area and trap air in their structure so their special odour receptors can interpret smells. Those olfactory neurons then send signals right into the brain via the olfactory nerve. The reason why we don’t experience a buildup of smells throughout the day is because of glands that secrete a type of protein-rich mucous that dissolves smelly substances after a short period. Regular flushing of the area keeps it primed to interpret new smells through the day. Beyond that, basal cells (a type of stem cell) actually replace the entire olfactory epithelium every 6 to 8 weeks.

Breathing, or, the respiratory segment. The nose’s architecture points to its superiority over the mouth in the breathing department. Humans are designed for predominately nasal breathing - it has far more benefits to our physiology than mouth breathing, which is a factor in declining dental and/or orthodontic, cranial, and even postural health, among other things.

Scroll-shaped caverns called turbinates or meatuses (what) create steady airflow over the most surface area, so all the functions of the nose can do their best work. Unlike breathing through the mouth, which provides no benefits whatsoever to the air entering the body, the nose works like a well-oiled (mucoused?) machine.

First, nostril hairs filter out large particulate to keep junk like dust out of the lungs.

Then, the textured, humid environment of the superior, middle, and inferior meatus brings the inhaled air up to about 98% humidity to protect the lungs.

With humidity comes a bump in temperature. Air held in the nose is at body temperature. As outside air passes through the passages and over cilia and nasal mucosa, it warms to about 33˚C. This is a mechanism in place so temperature differential doesn’t impact the ability of delicate bronchioles to function further down in the respiratory system. If they get too cold, they’ll contract instead of expand. Not so good in the lung department for the breathing.

Finally, a coating of mucous through the entire structure does even more filtration work. It traps finer particles down to 2-3 microns in size that get through the nostrils and makes sure they don’t make it any further. The mucous gets sent down toward the esophagus and into the stomach, where anything that’s trapped is broken down by stomach acid.

Circulation and the nasal cycle. There’s quite a large blood supply in the nasal region. The tissue in the turbinates is designed to grow and shrink thanks to an alternating bloodflow pattern on either side of the nose. Extra circulation enlarges one side, constricting air flow, while the other side’s tissue shunts blood away and widens the nasal passages. The cycle happens every two and a half hours or so as part of the autonomic nervous system, the same one that governs the heart and other unconscious bodily functions. The side that’s constricted gets to replenish its heat and moisture levels, while distinguishing smells that take longer to bind with receptors. The more open side is efficient for breathing and can snap up the faster-binding odours. The overall outcome is a nose that can identify a wider range of smells and process incoming air more effectively.

Now that we know about the main functions of the nose, there’s more to the story. What goes into making noses run in the cold? It’s mostly about the mucous. Surprise, surprise. But there’s also another component in play.

The human body creates between one and two litres of mucous a day, but it’s not all the stuff that gives us the sniffles. Instead of the goopy stuff of sick days, everyday mucous is quite thin. It lines the inside of the nasal passages and the larger respiratory tract as a membrane, coating the septum, the meatuses, and even the sinuses. When congestion hits, it’s not often mucous that’s causing the blockage; it’s more likely to be inflammation affecting the tissue in the nose. The same way the nasal cycle works, only as a result of allergies, viruses, or irritation. Noses, sensing trouble, make it harder for allergens and pathogens to enter the body by closing off the entrance.

As we now know, the purpose of all those structures is to filter out the bad stuff while prepping the air to enter the lungs. The nose is quick to respond if the conditions aren’t right. Too dry? More mucous. Too irritating? Close up shop. Sick? Everybody out. These processes happen almost instantaneously and are beyond our control. Chemical neurotransmitters are going wild when the body thinks it’s time to put up its defences. The same is the case for temperature.

As temperatures dip, humidity tends to dip as well. This has significant impact on how the respiratory tract responds to changing conditions. The regular cycle of recovering moisture on either side of the nasal cavity isn’t enough to prevent damage to the thin membranes separating blood vessels from the outside world. The nose has to overcompensate to protect itself.

So we’ve got humidity and temperature to contend with. Here’s the order of things when your nose decides to turn the faucet on in cool weather:

THE COLD HITS

Cold air meets body-temperature air in the nose, creating condensation. It’s simple water that springs up as a product of temperature differential between the outside air and the inside air. That dampens the situation right off the bat.

The meatuses begin to dry out and neurotransmitters sound the alarm to save the many capillaries in and around the nose. Here comes the mucous! The thin, clear variety shows up to keep the labyrinth hydrated, as well as to maintain moisture all the way down to the bronchioles.

The glands that produce mucous are doing so at body temperature, which helps to warm the air further as it travels down to the lungs. The cool air meeting newly warmed membranes mean even more condensation, and so the cycle goes on.

Experiencing a runny nose when it’s cold isn’t a sign to breathe through your mouth; it’s actually a signal that your nose is doing a great job of keeping your respiratory tract healthy. Where mouth breathing offers dry mouths and sore throats, nose breathing lubricates the entire system while protecting circulation and the immune system.

Round of applause for mucous, I guess!